On how I learned to do less, so I can "have it all"

Deep Work changed my life

I was a hyperactive, plausibly ADHD child. My mom honed a set of diplomatic skills that would make Henry Kissinger turn pickle green with envy just to get me to colour one cartoon at a time for longer than one minute and fifteen seconds.

Today, in adulthood, choosing one thing and shutting down all other stimuli continues to be a heavy lift. I’m excited about dozens of things on any given day. I often wake up with ideas flying in and out of my head like butterflies, confetti and shooting stars all at once. I have a new business idea every other week (I do not pursue all of them, thank God).

That, of course, causes me to:

Be involved in way too many projects

Run several teams and companies at once

Be on the board, advisory or some sort of active mentorship roles in several others

Work with too many people, in too many capacities.

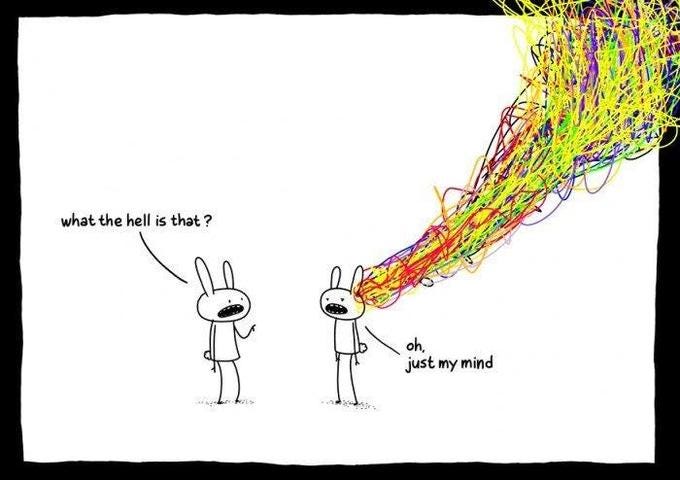

Which, in turn, causes my Gmail, WA, Slack, LinkedIn, Telegram, Discord inboxes and 84937942 tabs open to look and feel like this, first thing in the morning:

Yet, the one skill that has likely paid off most in my life, both personally and professionally, is focus and sticking with business ideas, relationships and projects for long stretches of time.

So when I read Cal Newport’s book Deep Work a few years ago, I was intrigued, offended and hooked. But what does deep work even mean?

Give me a minute, let’s first talk about the new economy.

The new economy

Newport, a New York Times best-selling author and professor of computer science at Georgetown University, believes there are two core abilities for thriving in the new economy: quickly mastering hard things and producing at an elite level, in terms of both quality and speed.

As machines get smarter, employers are more inclined to hire machines over people. Even when a human touch is needed, advancements in remote work tech make it easier to outsource roles globally, leaving local talent underutilized.

Deep work vs. shallow work

In this new world of work described above, “knowledge” workers are usually performing two types of work:

Shallow: Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend not to create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

Examples here from my own work include: responding to a quick email, creating an invoice, checking a report, organizing and cleaning my digital desktop.

But to remain valuable in our economy, you must master the art of quickly learning complicated things. This requires the other type of work:

Deep work: professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. This includes activities like strategic planning, coding, creative writing, deep research, mathematical problem-solving or learning a new skill.

The verdict is simple: If you don’t cultivate this ability, you’re likely to fall behind as technology advances. Deep work is not an old-fashioned skill falling into irrelevance - it’s an essential ability for anyone looking to move ahead in a globally competitive information economy that tends to chew up and spit out those who aren’t earning their keep.

Deep work is so important that we might consider it, to use the phrasing of business writer Eric Barker, “the superpower of the 21st century…”

In this context, Cal advances a hypothesis or paradox:

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy.

Actionable takeaways

Now, it's easy to praise the theoretical ability to stay uber-competitive by learning how to do hard things fast, to lament the threat of technology, and to rant about how everyone's attention span these days is similar to a squirrel’s (or the length of a TikTok clip). There is some kind of solace, but not much value in that. What I found truly useful from Cal’s work were the actionables.

The book is jam-packed with excellent insights, but here are the five that changed how I work and live:

1. Don’t live in your inbox

Many of us check our email the moment we start work, or perhaps much earlier, the moment we wake up.

Cals argues that there are a suite of problems with that. Our brains construct our worldview based on what we pay attention to. [...] “Who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love—is the sum of what you focus on.”

He quotes writer Winifred Gallagher who explains this is a foolhardy way to go about your day, as it “ensures that your mind will construct an understanding of your working life that’s dominated by stress, irritation, frustration, and triviality. The world represented by your inbox, in other words, isn’t a pleasant world to inhabit.”

The actions I implemented: I have no push notifications for new emails, and I have a few dedicated time slots to check and address emails. I go for the rest of my day not worrying about my inbox. I slip when I’m waiting for news or when I’m having a particularly tough day (there’s a dopamine release in quickly addressing an email and crossing it off your list, isn’t it?)

2. Schedule your day around focused work, not interruptions

Our workdays should be built and centred around deep work, not interruptions (meetings, appointments, social media, etc).

If you send and answer e-mails at all hours, if you schedule and attend meetings constantly, if you reply to messages within seconds, or if you roam your open office bouncing ideas off all whom you encounter—all of these make you seem busy in a public manner. But they don’t produce much value.

Like Roosevelt at Harvard, “attack the task with every free neuron until it gives way under your unwavering barrage of concentration”.

The actions I implemented: I start my day with a couple of hours of reading and writing, followed by a break for breakfast/fitness/checking my inbox, followed by another couple of hours of focused work. By the time I get to lunch, I feel like I’ve “achieved” a lot for the day, and I can then dive into meetings, inboxes, instant messages and so on.

3. Reduce the number of tools, networks and platforms you’re on

If you’re a knowledge worker—especially one interested in cultivating a deep work habit—you should treat your tool selection with the same level of care as other skilled workers, such as farmers and craftsmen:

Identify the core factors that determine success and happiness in your professional and personal life. Adopt a tool only if its positive impacts on these factors substantially outweigh its negative impacts.

Cal says that “the notion that identifying some benefit is sufficient to invest money, time, and attention in a tool is near laughable [...]. The question once again is not whether Twitter offers some benefits, but instead whether it offers enough benefits to offset its drag on your time and attention (two resources that are especially valuable to a writer)”.

The actions I implemented: I’ve taken a decision to only be reliably accessible and active on a few platforms, and communicated that with people I work with: Slack (where I communicate with my teams), email (addressing it a few times a day as mentioned). I use LinkedIn, Instagram and WhatsApp (I usually spend an hour on all of them combined a day), but do not have push notifications enabled, so I see them when I see them. The other platforms I had to create accounts on for different events, project or social requirements, like Telegram, Discord, Facebook: I check each of them only 1-2 times a week or sometimes even less frequently.

4. Implement a “shutdown ritual”

I know, this sounds a little crazy.

Early-twentieth-century psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, describes the ability of incomplete tasks to dominate our attention. In other words, when you start a task but don't finish it, it tends to stick in your memory more than tasks you've completed.

When you work, work hard. When you’re done, be done. What a refreshing thought in its impeccable logic and simplicity!

To get there, Cal proposes implementing a strict shutdown ritual:

In more detail, this ritual should ensure that every incomplete task, goal, or project has been reviewed and that for each you have confirmed that either (1) you have a plan you trust for its completion, or (2) it’s captured in a place where it will be revisited when the time is right.

Only the confidence that you’re done with work until the next day can convince your brain to downshift to the level where it can begin to recharge for the next day to follow.

Here’s another comforting thought: the idea that you can ever reach a point where all your obligations are handled is a fantasy. So yes, don’t feel bad when the day ends and you haven’t hit everything on your list!

The action I implemented: a “shutdown” ritual, and it’s become as indispensable to ending my day as brushing my teeth.

5. Embrace boredom & brain rest

Good sleep is another touchy topic for many of us (e.g. between 50 and 70 million Americans do not get enough sleep on a regular basis), and is seen as a competing “activity” to hustling more.

For the longest time, it felt like one had to choose between working hard, getting adequate rest and living a full life, accommodating for other components (family, hobbies, etc). Of course, in theory, you could have all these while hustling, but they were more of an afterthought, they couldn’t possibly demand of you any long stretches of time. You could only pick two. You might have seen a variation of this chart:

PICK TWO:

Cal slides right in and says:

“Regularly resting your brain improves the quality of your deep work. Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body […] it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done. […] trying to squeeze a little more work out of your evenings might reduce your effectiveness the next day enough that you end up getting less done than if you had instead respected a shutdown.”

And even more interestingly for some of us, is the role that sleep plays in decision-making (the most important skill and activity for leaders). Cal mentions the unconscious thought theory (UTT), which fascinated me. In plain words, the conscious mind is vital for decisions governed by strict rules, such as precise arithmetic calculations. The unconscious mind, however, excels in navigating decisions involving vast information and ambiguous constraints, like Google's expansive data centers, extracting valuable solutions from massive amounts of unstructured information.

So technically, if you want to be a good decision maker, sleep well.

An insight that blew my mind is Cal’s theory that jobs are actually easier to enjoy than free time.

“Like flow activities, they have built-in goals, feedback rules, and challenges, all of which encourage one to become involved in one’s work, to concentrate and lose oneself in it. Free time, on the other hand, is unstructured, and requires much greater effort to be shaped into something that can be enjoyed.”

This is likely why it’s so easy for so many of us to get completely lost in work, with often dire consequences.

The action I implemented: I prioritize min. 7h of sleep as a default mode (with the occasional sprint that has a very clear “expiry date”). I’m also routinely looking for opportunities to be bored - and to be honest, this one’s real’ hard 😆

How I now do less, so I can ‘have it all’

My journey down this rabbit hole, reading about Cal’s minimalistic approach, as well as other research and authors on the topic ultimately freed me from the tyranny of the always urgent inbox, the pressure of being on all social media platforms at once, and taught me the ultimate trick of shutting down and being truly done until the next day.

This semi-minimalistic approach brought me peace and allowed me to, ironically, do more, and more meaningful, instead of less.

The key message of the book is not about productivity hacks, but about how you can have it all (professional success, fulfilling achievements and a rich personal life), if you’re intentional and strategic about building your day and your habits.

I hope reading this sparks some ideas and does the same for you, too.

“Recognize a truth embraced by the most productive and important personalities of generations past: A deep life is a good life.”

- Cal Newport

Massive thanks to

, , , for idea sparring & providing feedback on this article.

Feels like you're already like Leonidas himself with everything you do (that pic about inboxes and open tabs made me LOL)! But I suppose he even needed to train from time to time. I like the idea of a shutdown ritual; I'm going to try this one out and see what happens. Thanks for sharing this and for the reminder that work doesn't have to feel like walking through mud!!